BLACK BOX: VIDEO, POETRY & ENVIRONMENT

Curated by Zina Saro-Wiwa

Boys’ Quarters Project Space is proud to present a trio of videos by three incredible global contemporary art voices: Kader Attia, Allora & Calzadilla and John Akomfrah. Mesmeric and poetic films that are in conversation with the idea of environment or environmentalism. We are also delighted to be presenting a dramatic takeover of the reading room by reknown Port Harcourt-based international artist, Diseye Tantua.

The Black Box* of the title refers to many things not least the way we have transformed Boys’ Quarters white cube space into a black one. A darkened room is an ideal space to show video though it is by no means the only way to experience video art. But the black cube elevates our internal machinations when confronted with art. Therefore this strategy was chosen to allow the internal landscape of each viewer to interact with the works with little distraction. And it is the internal landscape we at Boy’s Quarters continually seek to engage and transform.

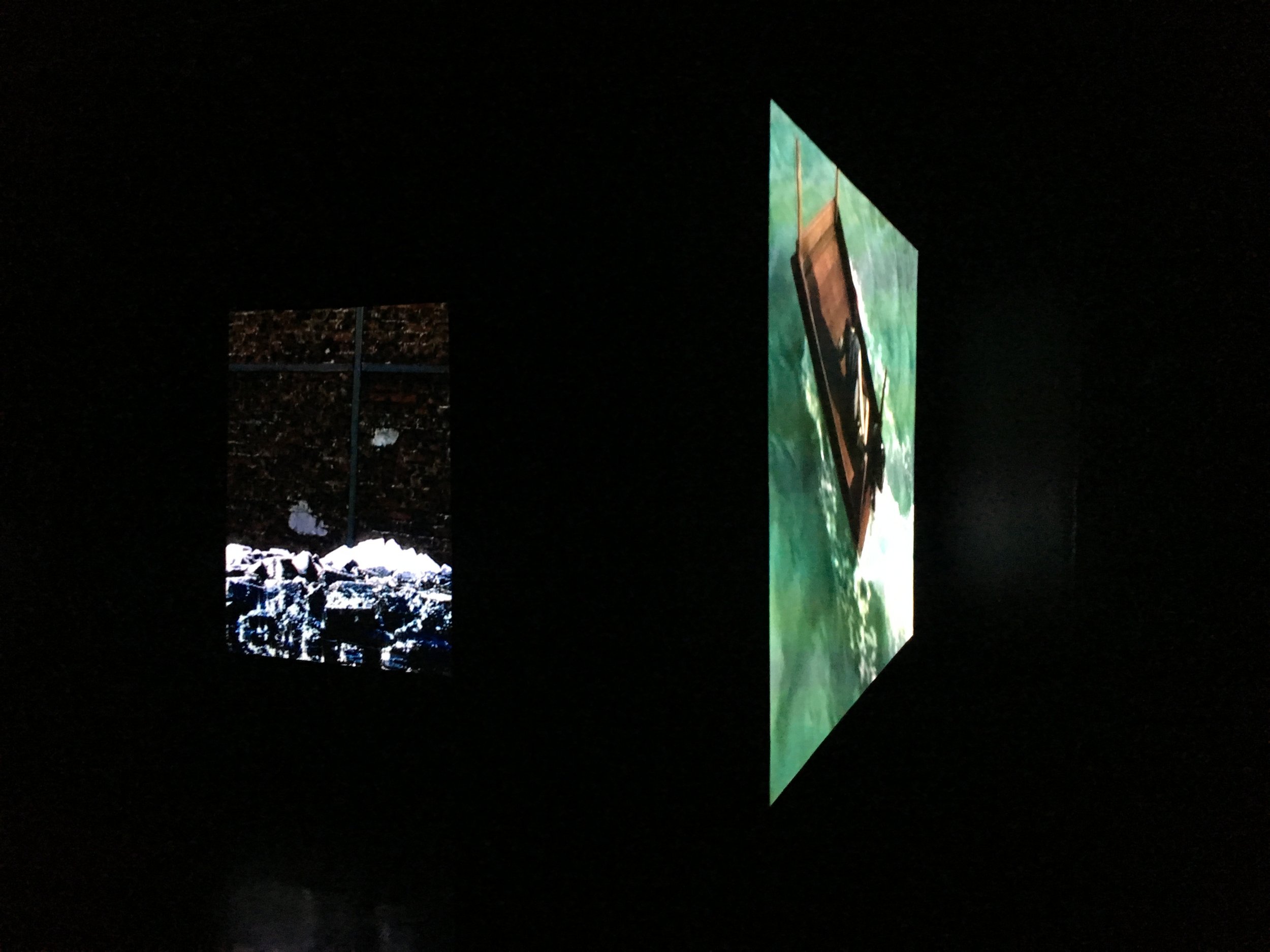

In the main gallery we are screening the videos Oil & Sugar 2, Under Discussion and The Call of Mist, films that relate to the environment in strikingly poetic ways. Puerto Rican artists, Allora & Calzadilla’s 2005 video Under Discussion is one that speaks directly to the Niger Delta experience although it was created in response to an environmental crisis at Vieques, a Puerto-Rican island. Vieques Island is a former military base which had been used to test noisy and dangerous military weapons. The island is scarred with bomb-craters and suffers a contaminated ecosystem. Although designated a federal wildlife refuge this action has enacted a new violence due to the fact that local voices had not been consulted and were not included in this decision making therefore stymieing efforts to monitor the apparent decontamination effort. This lack of consultation provided the impetus for Under Discussion which features an overturned conference table that has been retrofitted with an engine and rudder grafted from a small fishing boat. A local activist uses the motorized table to lead viewers around the restricted area of the island, re-marking the antagonisms that haunt the picturesque coast and bearing witness to the memory of the Fisherman’s Movement, which initiated the first acts of civil disobedience against the ecological fall-out of the bombing on the island. The hybrid device explores the absurd political inequalities of the situation: the table, a common trope for the non-violent resolution of conflict, is forcibly reliant on local navigation. The dissenter on a speedboat - a familiar trope in the Niger Delta - is striking for his almost military lack of emotion. Yet a powerful performative gesture is elicited from the act of demarcation created by his journey. This action and this video is drawing the lines of battle and marking the territory of democracy.

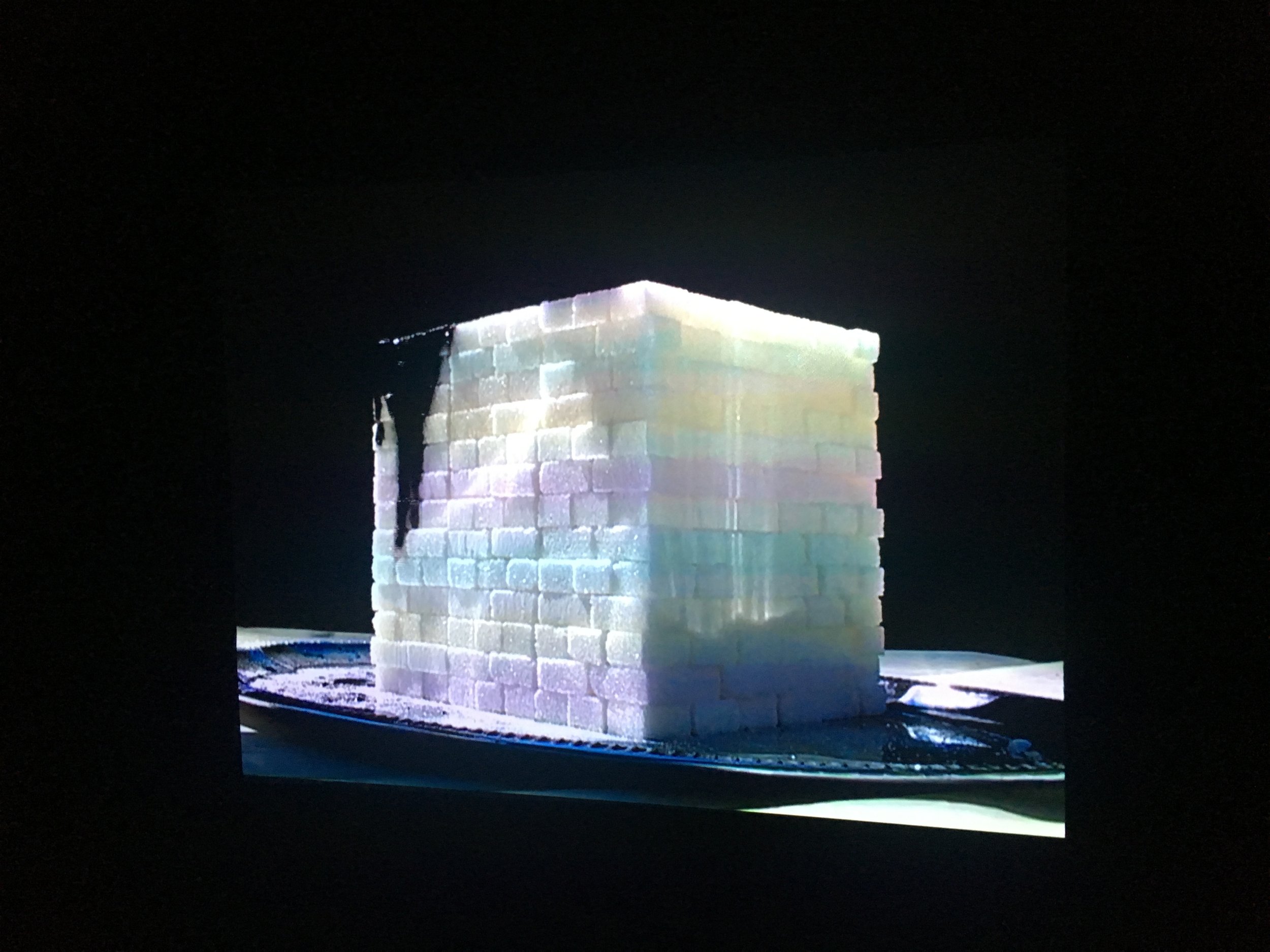

Algerian artist Kader Attia’s piece Oil & Sugar 2 (2007) features a simple yet profound gesture where two very recognizable and historically powerful commodities create a poetic motif when introduced to one another. The film starts with a pristine white block made out of sugar cubes shining in the sunlight. Black petroleum oil is introduced to the scene and is poured over the block. As the cube absorbs the liquid, it blackens before quietly but decisively dissolving. Acerbic, poignant and magical, the language of this visual poem fizzes. Ideas about the demise of infrastructures and the historical and present day effects of the political ecologies of these commodities may leap to the front of the mind but it is in the primordial soup which comprises almost half the film where the molten sugar and oil bubble and intermingle that provide some of the most absorbing and fecund moments in this film. A time and space to contemplate. A place to even feel hope. What can this poetic destruction produce?

The Windowall Gallery, Ken Saro-Wiwa’s former office, hosts a film made by John Akomfrah titled The Call of Mist (1998). With this film we encounter a different kind of poetry. Elegiac and full of longing, the human protagonist in the film is weighted with emotion: desolation and isolation. And yet he is not the only protagonist for the landscape, the mountains, the lake and the mist are all actors in this cinematic world. The landscape is not one that is close Akomfrah’s West African origins, yet it is a landscape that is a part of his being. The Scottish Isle of Skye, is a place he visited often with his beloved late Mother, Grace Akomfrah. John has made many trips to the Island and its dramatic landscape has become an important feature of his films over the years. The incorporation of this landscape leads one to think about psycho-geographies and contemplate the ways in which landscape and memory meet and how landscapes exist inside us and alter our internal geographies. Made in memory of the artist’s mother Grace Akomfrah, The Call of Mist is a vivid reflection on loss, memory and media. Hosting the film in the Windowall Gallery, Ken Saro-Wiwa’s former office, provides extra poignancy. The space is a site where Ken’s legacy is explored but also the very idea of memory itself is interrogated. It is in this space and through Akomfrah’s exquisite visual poem that we encounter memory as emotional landscape and we experience how it forms a part of our psychic ecosystem.

Connecting with a deceased parent is a motivating factor in one of the works in the dramatic takeover of the reading room. With it’s new red floor, stain glass windows and wooden furniture made out of a repurposed wooden boat and a beach shack from Prampram beach in Accra, Diseye Tantua has stated that it was during his time buying this house and boat in Accra and taking it apart that he realized the was trying to reconnect with his past, his father. The wooden benches and the table you see in the reading room were originally found on a boat. The table and benches are accompanied by two black and white photos and a video shot and edited on the artist’s iphone.

Diseye finds a dizzying poetry in the seascape of his mother’s native Ghana. A direct relationship to the sea that is not found to the same extent in the riverine yet coastal Niger Delta, his other home. Diseye talks of watching the young boys playing on the beach and in the waves, observing the market women waiting for the fisherman to bring in their haul and stripping off to enjoy the sun and the atmosphere. It is in this place and this moment that he encounters a wooden home on the beach that are full of the aphorisms and sayings that he is so enamored of and that find his way into his work so often. He then witnesses an inscription on a fishing boat coming in to shore that says “Isaiah” his late father’s name. He bought both the boat and house, had them stripped down and transformed the wood into furniture some of which you are witnessing in the space. Diseye ingests the landscape and transforms and repurposes it. A consummate artist he is constantly testing and asking questions of the environment around him. His

persistent questioning, positioning and repositioning, his relentless search and desire to translate the world and have it converse with him speaks to the conductive and transformative role the artist is supposed to play in the world. His views on the role of the artist are apparent in the stained glass windows he has installed. Though they cover metal bars (found in most homes in Nigeria) they are an attempt to sing despite the difficulties. The first panel features an image of Abraham about to sacrifice his son before God stops him, providing him with a sacrificial ram. The second panel features Jesus being sacrificed on the cross, the third panel is of man’s struggle to gain freedom and the fourth panel features Nigerian cultural icon Fela Kuti and his sax. The path to creative freedom requires struggle and sacrifice the series seems to suggest. But creativity is the key to survival itself for Diseye.

Boys’ Quarters Project Space exists to explore the relationship between self and environment in radical ways and declare art to be the fundamental medium with which to explore this relationship. We understand that environmentalism means more than simply dealing with oil pollution, plastic detritus or melting ice caps and are seeking to uncover and establish a deeper intersectional ecological truths that reveal how we are truly embedded in this world. These four works of art presented in Black Box come together to help us navigate this complex terrain. The works exhibited attempt to straddle the local and the international and encourage the definition of environmentalism from the perspective of the global south.

* A Black Box is a space of unknowing. A entity or object that has no immediately apparent characteristics and therefore has only factors for consideration held within itself hidden from immediate observation. The observer is assumed ignorant in the first instance as the majority of available data is held in an inner situation away from facile investigations. The black box element of the definition is shown as being characterised by a system where observable elements enter a perhaps imaginary box with a set of different outputs emerging which are also observable.